Creative Responses and Written Commentary (SOIs) Explained

The creative task – many students’ relished chance to set aside the rigour of textual analysis in favour of original and imaginative writing. Whether you’re someone for whom creative writing comes naturally, or someone who likes to have a bit of a methodical structure to start you off, this guide will distil the task down to the essentials and equip you with the skills to write a killer Creative!

What’s so special about the Creative SAC?

Unlike the other Areas of Study (Text Response, Comparative, and Argument Analysis), the Creative SAC is unique in that you are given free reign over what you may write on. You are generally given the creative licence to compose pieces such as a missing chapter, a particular scene from a secondary character’s perspective, or even a journal entry revealing the protagonist’s innermost thoughts. Note, however, that this is a very school-dependent task and teachers may instruct you to respond to a very specific prompt, or alternatively provide a broad topic to which you may write your response.

Nevertheless, you are assigned the role of the author now – instead of analysing someone else’s techniques, narrative construction, characterisation, and symbols, you are creating your own, and extending upon those already existing in the source material. In this way, we can think of the Creative as an opportunity to emulate the language techniques and devices of the original author, while having something additional to say about the big themes the author explores. For reference, you are usually given 800-1000 words in total for the original writing section of the Creative.

Approaching the task

Step 1: Create a plan for your creative piece

As with any piece of writing, the first and foremost step is to plan it out. Because of the breadth of possibilities inherent in this task, the planning process is especially important – I’d even go as far as to say that this is the most crucial stage, because this is where you are able to condense all your ideas and begin to establish the foundational narrative features of your piece.

Brainstorm

It is firstly a good idea to create a rough brainstorm of potential ideas for your Creative piece. This can include characters, themes, and plot points. You should consider what the main message of your piece is, and what you want to convey to your audience. In particular, there might be a particular idea the original author touches on that you’d like to further explore. It’s also great to start thinking about your target audience and what kind of story would resonate with them. For example, George Orwell, in his famed novel “1984,” creates a dystopian society where the government has complete control over citizens' lives, exploring ideas such as totalitarianism, government surveillance, and manipulation of language.

Once you start to have a general idea of the gist of your story, you should identify any narrative gaps that are present in the original text. These are excellent opportunities to further flesh out the world of the text and will contribute to giving the reader added insight into a particular character or scene. These gaps could include anything from missing plot points and underdeveloped characters, to unresolved conflicts and scenes that are referred to but not explicitly explored. To use an illustrative example, in F. Scott Fitzgerald's "The Great Gatsby," one narrative gap is the mystery surrounding the main character, Jay Gatsby. Throughout the novel, his past and background are not fully explained, leaving the reader with a sense of intrigue. A potential creative idea could be to write a chapter detailing his adolescence from the perspective of a young Gatsby – such a piece would require some imagination and would give readers that extra insight into his character and values.

Narrative Elements

Symbols

As with any text, symbols should be rife throughout your piece. While in the Text Response, you are analysing the implicit meaning and connotations of symbols the author has used, now you are injecting those symbols in your own writing – it’s kind of like the inverse. Symbols could be objects or motifs with a particular significance and representative value relating to a key theme in the piece. They add depth and meaning and can enhance the story and its themes. I like to think of them as vehicles through which we can communicate our message to the audience. To use an example from Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the symbol of the mockingbird represents innocence and injustice. The character Tom Robinson, who is falsely accused of rape, is compared to a mockingbird because he is innocent but still punished. The symbol of the mockingbird adds depth to the story and enhances the theme of racial injustice.

Settings

We should also consider the setting. Now, this doesn’t just refer to a geographical setting, i.e. where the story takes place, it also refers to the temporal setting – the time period and era the piece is set in. Both types of settings will inform characters’ beliefs and actions, and hence are essential in providing the backdrop for your story. It’s also important to note the effect the setting has on the piece’s overall tone. In J.D. Salinger's "The Catcher in the Rye," the setting is New York City during the 1950s. The city's fast-paced, gritty atmosphere reflects the main character's alienation and disillusionment with society. The setting plays a crucial role in shaping the tone and mood of the story.

Themes

Now that we have established a few main narrative elements, we should draw our attention to the issues and messages we want to address – these are overarching themes that the author examines in their original text that we want to say something further about. A hint: usually each character in the text will connect with a particular broader theme; we can expand on this to base our entire piece on this key theme to really make an insightful commentary on an issue relevant to the source material. Make sure these issues and messages are woven into the story in a way that is both meaningful and impactful for audiences. For example, in Jane Austen's "Pride and Prejudice," the issue of societal expectations and class distinctions is explored. The novel's message is about the importance of understanding and overcoming one's own prejudices and biases in order to achieve true happiness. The issue is woven into the story through the interactions and relationships of the characters, particularly the relationship between Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy. Throughout the novel, they both have to confront their own prejudices and societal expectations in order to recognize and accept their true feelings for one another. This theme is central to the story and is one of the main messages that the author wants to convey.

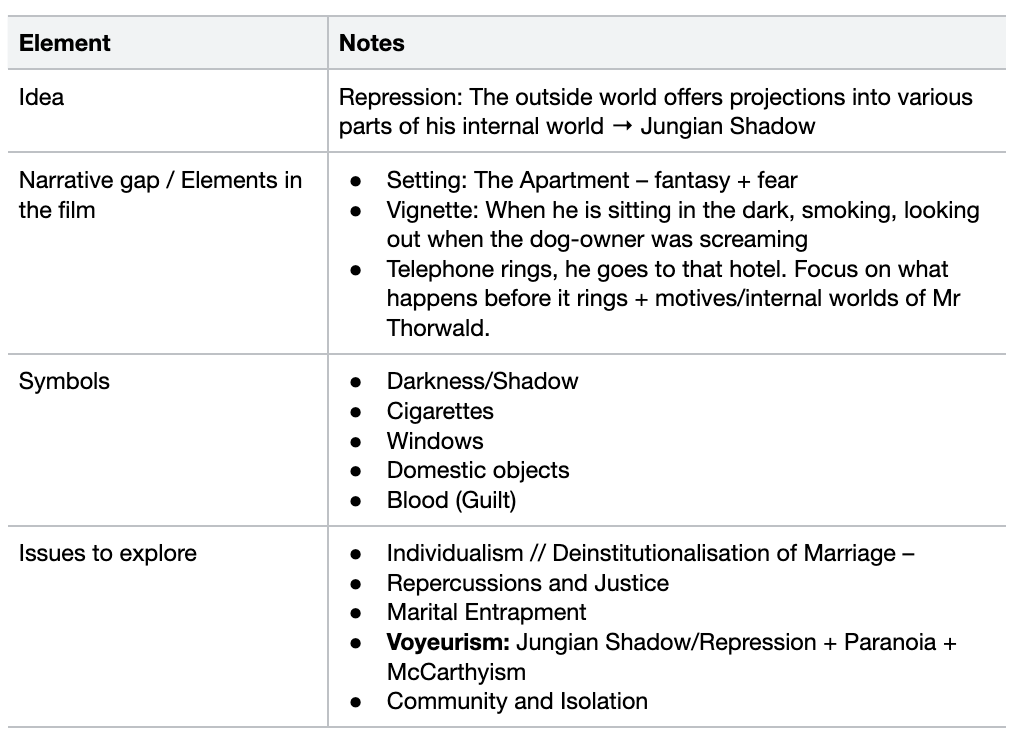

Once we have these ideas sorted, I would recommend making some kind of table to organise our thoughts and cement these narrative elements before we begin writing. Below is an example of a planning sheet you may like to use (based on “Rear Window”):

Planning sheet

Step 2: Storyline and techniques

With the most crucial and perhaps time-consuming step completed, we can move on to the actual writing process. This involves creating a step-by-step scaffold of the main plot – the storyline that our piece will follow. Remember to avoid over-complicating this – while the tangible events that occur are indeed important, we are going for a complexity of ideas and messages rather than a complexity in plot. We want to make sure the reader can still follow along, armed with the background knowledge afforded by the original text.

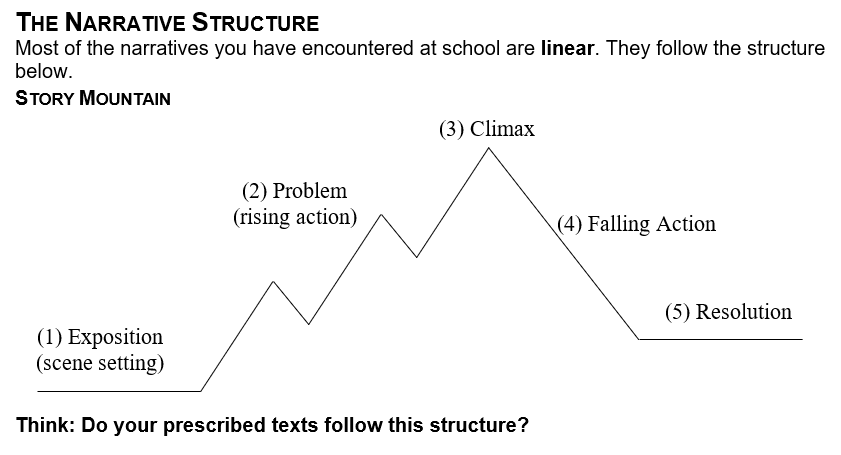

It’s good to keep in mind the fundamental narrative structure – this is one that you have probably seen in lower year levels, but still stands well today! We firstly begin with an exposition, which essentially amounts to scene setting as well as establishing context and background. Then, problems and issues begin to emerge and build up, until a climax is reached. There is then a “falling action”, where plot points and intricacies begin to resolve, until we reach the very end with the final resolution.

We do also need to consider the perspective from which we write, as this will heavily impact the readers’ degree of insight into the events that occur. The main perspectives in narrative writing are listed below – note that no perspective is right or wrong, and can be utilised to leverage the story depending on your desired purpose.

- First person - Using personal pronouns “I”, “My”, and “Our”. This mode of writing is the most immediate way the reader may access a character’s thoughts and feelings from a very intimate, personal point of view. Reflective pieces, journal entries, and memoirs would use this perspective.

- Second person - This is less common, and uses words such as “You” and “Yours”. Essentially, this is more of an instructional perspective in which the narrator is telling you, the reader, to feel or act, as if you yourself are the one in the story. Such a perspective is transportive, and directly involves the reader in the narrative.

- Third person limited - This is a far more common one. Here, we use pronouns like “He” and “His” to tell the story. It is limited because the narrator only can reveal the perspective of a single character – they would not know what another character on the other side of the world would be thinking, for example.

- Third person omniscient - We use the same sorts of pronouns here, but instead of being limited in our perception of events, we now have an all-encompassing awareness – we are omniscient, meaning the reader has access to all events and characters in the narrative.

Below is one example of a storyline for a potential creative piece, at the planning stage:

Scene: Mr Thorwald sitting in the dark – the voice of the dog-owner becomes blurred

- View of the courtyard

- He is watching others from his windows (distracted/accidental encounter)

- Analyse one observation – how that represents his subconscious fears or desires (Ms LH)

Next Day: Describe the apartment

- Cleaning out the blood/spots (guilt/symbol)

- Visual imagery: What does the apartment look like? Has it changed [in his mind] since his wife’s death? Does it still remind him of his guilt?

- Cross-cutting between this and also his fantasy about freedom

- Thorwald packing

- Smoking the cigarette

- Looking around for culprit

- Allusion to the affair

- Picks up white hat & leaves

Climax: The telephone rings

- Build up suspense

- He starts becoming paranoid, maybe he actually brought a weapon into his meeting with this anonymous killer?

- Confrontation with the wrong guy, dragged into that alley, only to find out about two unwelcome visitors

- The guy is innocent, maybe a sentence of two of dialogue

End: Inescapable nature of his guilt

- Paranoia

- Semi-unresolved ending

- end with him opening the door to his apartment?

- or with him discovering Lisa and assaulting her

- or with police arrival

Writing the Creative

Now we are ready to move on to the writing of our Creative. A great technique I like to use is called in media res, roughly translating to “starting in the middle of the action.” This approach, used at the beginning of a piece, immediately immerses the reader in the narrative, allowing them to piece together information from hints we are giving them throughout our writing. The contrasting approach would be to explicitly state every single detail about the context from the get-go, which may dilute the impactfulness of your writing. An example is shown below:

Shattered Looking-Glass

The photograph is torn and stained, coated with a layer of cooking grease. It has been there for a while, dangling by one corner, but never falls onto the ground. The woman photographed looks perfect in her green shantung dress; not a single loose strand of hair falls from her perfectly sculpted bob; no sign of age, loneliness or exhaustion can be found on her face. I study the photo meticulously, coating my face with a thick layer of beauty powder until I look like her looking-glass.

After putting on a similar-looking green dress, albeit made of a different, less expensive fabric, I fix my hair, adjust my hat, put on the only pair of gloves found in my drawer and settle my nerves with a glass of gin. Walk like a lady, not like the undesirable woman you are so bent on becoming. I nervously leave the house for my date with John.

Written by a past student (study score: 45)

In this extract, we are beginning by detailing the “torn and stained” nature of “the photograph” - an item to which the audience is previously unacquainted with. In doing so, we create a sense of intrigue and suspense - the audience may think, “What photograph? Why is this important?”, implicitly drawing in their interest. A similar mode of information-hinting is used as we mention “the woman photographed” as well as in our reveal of the narrator in “I study the photo…coating my face with a thick layer of beauty powder.” That we do not mention any names or events only serves to further this sense of curiosity in readers.

This sample also exemplifies the use of italics when the central character is monologuing. Such a technique is seamlessly woven within the rest of this paragraph in “Walk like a lady, not like the undesirable woman you are so bent on becoming.” Being written in first-person, this piece already gives readers a close insight into this character’s thoughts - the inclusion of her italicised inner-voice creates an even more intimate perception into her psyche.

A lot of students struggle with striking the ideal balance between reflective description and events. This is particularly the case if a character is monologuing – in this case, we do want to hear the character’s private thoughts, but also have something going on in terms of action and events – just to round it out for a fully complete piece.

The Statement of Intention

This is a crucial part of the Creative task, in which you are to clearly and concisely justify the writing and creative decisions you have made in about 200-300 words. As the Statement of Intention (SOI) is usually read first before the Creative by your teacher, it is essential to provide all necessary background so that the reader knows how your piece fits within the context of the source material. There are a number of key elements to include in the SOI, and I like to use an acronym to remember these.

FLAP-C

This stands for Form, Language, Audience, Purpose, and Contention.

Form

The form of the piece refers to the genre and style you are writing in – whether it is a poem, newsletter, or diary entry. You must discuss what perspective your piece takes, as well as why you have chosen to use that particular perspective. If there’s a title, explain why you have named the piece that way too. The tense is also included under this heading.

Language

Language choices and decisions can be both on a macro and micro level. Regarding the macro, or broad, level, you can justify your use of overall language style, e.g. “I have chosen to use language befitting 17th Century England as that is when my story was set”. As for the micro, or specific, level, you can explain your inclusion of particular words or phrases, e.g. “In having the protagonist of my piece say [quote from the Creative], I aimed to explore their internal thoughts in…”

Audience

As mentioned previously, your intended target audience must be a very specific demographic (as with the original author). For example, “those already acquainted with the world of the text who desire a deeper understanding of [secondary character], being that they were underdeveloped in the original text.”

Purpose

This aspect seems to stump a lot of students, but essentially, your purpose refers to your own authorial intent – your take-home message you want to give readers. This may be to further advance the issues in the original text, or to provide an alternate perspective to an existing theme. Make sure to link this expressly to the high-level themes the author discusses.

Context

The context refers to where the piece is set within the world of the text – what chapters or sections are directly preceding and following your piece? Where are the characters when we first begin reading the Creative? Answering these questions allows us to provide readers with a crystal-clear picture of what they should be expecting going into the piece. Context may also refer to the socio-historical context, which relates to that of the source material.

Below is an example of an SOI plan (again, on “Rear Window”) which outlines the main points of justification you may like to include. Notice how the student has mentioned both holistic and close analysis, as well as linked their piece to relevant ideas (such as “Freud-Jungian theories” and “intra-household conflicts”) found in the original text.

Introduction:

Form:

- Narrative prose - short story; with the characteristics of a journal entry;

- First-person narrative

- Suspense & Crime fiction

- Chronological

- Insertions of inner thoughts and vignettes

Theme & Character

Marital entrapment explored through the perspective of Mr Thorwald

- Fermented enmity of Mr Thorwald; frustration, claustrophobia, discontent

- Motif of doubles (doppelganger) - Jeff as Mr Throwald’s double - likening physical entrapment with confines existing in his internal world

Social context

- Deinstitutionalisation of marriage

- Authorial intent (anti-suburbanism; anti-urbanism; URBAN c.f. PASTORAL/RURAL

- Advocates against domesticated lives - monotony and mundanity of married life

- Dramatise intra-household conflicts

Holistic analysis (narrative voice/stylistic features)

- Overall: Title/narrative style and perspective (profiling of a murderer)

- Filling in the narrative gap

- Narration: First-person + free indirect discourse (stream of consciousness), vignettes, etc

Close analysis (x2)

- Use quotes – discuss the inclusions of certain words (i.e. Diction)

- Literary devices (syntax, polysyndeton vs asyndeton, inner monologue, dialogue, metaphors, stream-of-consciousness, run-on sentences)

- Freud/Jungian theories

- Significance of the quote, link it to the themes of the text

To formalise our justification into a Statement of Intention, we must combine the different elements of FLAP-C into a coherent, concise piece of writing. Let’s look at how we might go about structuring this.

It is firstly an excellent idea to begin by introducing the overall form, style, and genre of the piece (as well as a title if you have one). This immediately allows your reader to get an idea of what your piece is about, as well as the broad creative direction you have taken. The following extract is a scaffold for the beginning of a potential SOI:

My creative piece [title] adopts the literary form of a two-part short story/narrative prose, transitioning from a [setting 1] to the [setting 2]. The use of a chronological/non-chronolgical structure and stream-of-consciousness narrative style are characteristics resembling a series of journal entries, and a [narrative voice] from the perspective of [character] enables [thematic ideas] to be more deeply explored. The genre of drama is developed through the adoption of [genre] tropes and the insertion of vignettes and vivid imagery.

We have started off by explicitly labelling the literary form as either a “two-part short story” or “narrative prose” - both descriptions are highly specific and precise (compared to calling it a “chapter” for example). Whether the piece follows a chronological or non-linear structure is also something to keep in mind, and is important to preface to your audience before they read your Creative. Note as well that we have elaborated on our use of the “drama” genre, backing up this claim with evidence that we have “adopt[ed]...tropes” unique to that particular genre and style.

Though the Creative Task is often one that many students would like to “get out of the way” as quickly as possible, the skills developed in written expression as well as being able to reflect on the author’s ideas will prove invaluable in your study of English as a whole. We hope that this guide has given you a heads-up on what to look out for, and how to plan and structure a great Creative piece!